By Mike Anglin

Hon. Jerry Buchmeyer, U.S. District Judge

A tremendously important chain of events began in Dallas in the early 1980s, spanning a period of about 9 years, known as the Baker vs. Wade case. This was a matter of federal litigation which took place in the United States District Court in Dallas, addressing the question of whether or not the United States Constitution did, or did not, permit states like Texas (and a majority of the other states) to criminalize adult, private, consensual sexual relations between persons of the same gender.

Before addressing how this litigation came about, and the results achieved, it is essential to understand why it was so important.

In Texas, Penal Code Section 21.06 made sexual relations between two people of the same gender a class-C misdemeanor, punishable by a fine of up to $500. Literally, 21.06 criminalized "deviate sexual intercourse" between two people of the same gender. Importantly, what was carefully defined as “deviant sexual intercourse” between two people of opposite genders (assuming those sex acts were consensual, between two adults, and in private) were never criminalized.

Were same-sex couples arrested and fined for violating 21.06? No. In all of our searches at the time, we could never find a single instance of an arrest, much less a prosecution, for the violation of this Penal Code provision. In fact, “prosecution” was never the real point. The effect of the law was to paint an entire subculture within the population of Texas as “admitted criminals” in order to justify many forms of discrimination against the members of that population.

For example, if it were discovered that a teacher in the public schools was gay, that teacher would be fired – not because he or she was gay, per se, but because he or she was an admitted criminal (albeit a minor criminal, given the “Class C” nature of misdemeanor). "Surely no one is advocating that we should allow an admitted criminal to be teaching our innocent children!" would be the common refrain.

If a gay couple applied to lease an apartment, they could be rejected by the landlord, not really for sexual orientation. "But surely no one is suggesting that a landlord must rent space to admitted criminals. We have our standards!"

If an openly gay man or woman wished to apply for employment in a city police department or fire department, a city ordinance would prohibit such a hiring on account of the applicant’s open admission that he or she was a practicing criminal. "Don’t take it personally. It's not because you're gay; it's because you admit that you are a continuing and unrepentant criminal. That disqualifies you for any kind of law enforcement work."

Thus the problem. As long as 21.06 was on the books as a crime in Texas, it would serve as an easy pretext to excuse any form of inequality experienced by gay citizens of the state of Texas – in both the private and public sectors – and no proposal for non-discrimination laws or ordinances would ever gain traction in the public discourse.

The effect of this statutory ‘blessing of discrimination’ against all gays ricocheted throughout the community. In 1976 the Dallas Police Department’s patrol officers and vice squad officers routinely recorded the license plate numbers of individuals who attended gay churches or gay bars – the only purpose being to intimidate and harass.

The Dallas “motion picture review board” added a category of “P” to their movie rankings, for use in warning parents of any movie that featured a same-sex relationship (portrayed negatively or positively – didn’t matter) or even contained a discussion of the issue. The “P” stood for “perversion.” Most movies of the day that did feature homosexual characters portrayed them as either repulsive predators of innocent, attractive younger characters, or as deeply disturbed (psychologically), usually either homicidal or suicidal, take your pick. The rule of thumb was that any featured gay character in a movie must either be killed off, commit suicide, or at least long for an end to his or her crushing misery. Examples are: The Sergeant, Boys in The Band, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, Cruising, Looking for Mr. Goodbar, Rebecca.

Section 21.06 was always used to justify these measures on “crime fighting” grounds, so, as a Texas criminal statute, it had to be destroyed in the courts before any real progress toward equality and enlightenment could be achieved.

Could that be done politically? There were some prominent state politicians, like Atty. Gen. Jim Mattox, who were highly critical of Section 21.06, seeing it for what it was: a justification for blatant discrimination. But the great majority of elected officials at city, county and statewide levels had zero interest in taking up this unpopular issue on grounds of basic social justice. Too much was at stake with their constituencies. That meant that the best hope of removing 21.06 would be by judicial action, in the courts, applying the supreme law of the land, the United States Constitution, to set aside the statute.

Mort Schwab

So, in early 1976 four gay activists in the city of Houston created an organization which they called the Houston Human Rights Defense Foundation with the principal goal of attacking 21.06 in federal court. Those individuals were Mort Schwab, Gary Van Ooteghem, Keith McGee and Gary Rather – with Mort Schwab taking the main leadership role.

After a couple of disappointing years, getting no meaningful support for the project, they decided to expand the organization by enlisting board members in Dallas, Austin and possibly San Antonio. In June 1978 they changed the name of the organization to the Texas Human Rights Foundation (or “THRF”), and began the search for new board members to represent the other cities.

In Dallas, Mort contacted my old friend Dick Peeples, who agreed to join the new state-wide THRF board – the first board member from outside Houston. Peeples then reached out to me; I agreed to join, too. We then called our fellow-attorney friend Lee Taft. He, too, agreed to join the THRF board. Mort Schwab became president of THRF; I agreed to become vice president, and Dick Peeples became treasurer (all of which signaled the sincerity of the original Houston directors that THRF indeed be a multi-city/state-wide organization – the first of its kind in Texas).

With the new board in place, and the board members ready, willing and able to travel to each other's cities for a series of planning sessions, it was agreed that a case should be initiated in a federal district court (possibly in Dallas) seeking to declare 21.06 unconstitutional. We chose the federal courts because of the developing law on the “Right of Privacy” under the Constitution – something not expressed in so many words in the Constitution, per se, but which the justices on the Supreme Court had been finding to exist, in other cases, as an underlying illumination of the Bill of Rights (giving rise to the concept of a “penumbral” right of privacy). This new approach to understanding the Constitution had been the basis of Supreme Court decisions setting aside, for example, a Connecticut law which prohibited doctors from advising their patients on effective contraception, and a Virginia law which forbade interracial marriage.

Once the decision was made to initiate the case in Dallas, it became clear that the Dallas contingent on the THRF board (Peeples-Anglin-Taft) would be the hands-on, day-to-day managers of the litigation on behalf of THRF. Why was Dallas chosen as the best "location" for the litigation? For one reason, the Dallas GLBT community was arguably, at that time, the most organized and capable in the state. The only problems presented were that we had no plaintiff, no trial attorney, no expert witnesses, no public awareness, and no money (for which there would be great need).

Jim Barber

Dick, Lee and I figured that step number one was securing a capable trial attorney. We could use his or her help and guidance in organizing the rest of our efforts, staying on task, and creating the long to-do list in preparation for bringing the case to court, hopefully before the end of 1979. I contacted an attorney friend of mine named Don Maison, a well-liked and widely respected member of the gay community in Dallas, and I asked him if he knew of anyone who would be capable of handling this kind of federal, constitutional litigation in the U. S. District Court in Dallas. He recommended a friend of his named Jim Barber, a tough, effective trial lawyer with an all-American wife and family, and openly liberal leanings. We met with Barber, and he ultimately agreed to take on the case under a reasonable compensation scheme. It was not to be a “pro bono” case, as such. He probably charged us a lot less than he would have charged a regular client, but there are many fixed costs in civil rights litigation, and we did need to raise money to pay him for his services. He made a convincing argument that it was the gay community who should be willing to “foot the bill” for this litigation, not just his law firm, and not just the board members of THRF. We agreed that this made sense, but clearly that put the onus on THRF’s board members to get out into the community and raise money to cover legal expenses.

While “overturning 21.06" was the unrelenting battle cry of THRF, that was not the only purpose behind the litigation. We wanted the process to foster a new empowerment of the GLBT community in Texas, and be an effective means of educating many Texans on the long-shunned and somewhat indelicate legal issues raised by sexual orientation. The case would need to mobilize the many distinct “gay communities” in the state (including many of the smaller communities in south and west Texas) and open new channels of communication between and among them. Our fundraising events would hopefully lift the spirits of everyone who participated, gay and straight, and show that, by pulling together and contributing whatever we could, a better life could be created for future generations.

Jim Barber gave us his advice on what kind of individual would make the ideal plaintiff in the case. It would have to be someone very “presentable” and willing to be the public “face” of the litigation, since there would likely be a good deal of media attention (some of it hostile) as soon as the case became known to the public. It had to be someone who was articulate, dignified, respectable, well-versed (or at least trainable) in constitutional issues, well-liked and admired in the community (to help secure the donations we would need), and ideally someone who had already experienced the discriminatory side-effects of the statute and/or would be likely to experience that kind of discrimination in the future. Needless to say, this was a tall order.

We all began discussing who might fit that profile, but no answers emerged easily.

It is hard to adequately describe, today, just how reviled and vilified our plaintiff would be in the public eye of 1979 – most likely to be portrayed as a disgusting, immodest pervert seeking to have his obscene and sinful “sex habits” blessed and dignified by the public courts. Preachers across the city would likely hold forth on how this one individual symbolized the end of western civilization. Has he no shame!?

Times truly changed over the next 35 years.

I rarely went to “the bars” on Cedar Springs Road to socialize with friends, but occasionally a group of us would put together an outing to go check out some newly opened dance hall or saloon. On one such evening some friends and I were checking out a new "western" dance hall on Cedar Springs named "The Roundup." At some point that evening I bumped into a good friend named Don Baker whom I had gotten to know when he became the new vice-president of the Dallas Gay Political Caucus where I was serving as board advisor and “parliamentarian” [Don and I later realized we had actually met in college at East Texas years earlier, but had never become friends at that point in time]. He and Dick Peeples were close friends, as well. I decided to let him know about the plans of THRF to initiate a major federal court litigation case to attack the constitutionality of 21.06. At first, I thought he might simply be a worthy resource, perhaps with some good ideas on who might make a “perfect” plaintiff for the case. But the more we talked about it that evening, over several beers at the bar, the more I realized that I was looking at the perfect plaintiff in the case. Once I was sure he understood what the case was about and who we were looking for, I said: "Don, the truth is, you would be the perfect plaintiff for our case if you’re willing to put yourself out there in the public eye that way."

Dick Peeples (left) - - Don Baker (right)

Possibly without thinking it out very carefully, Don responded, "Okay, well, I'm honored that you would ask, and if you sincerely want me to be the plaintiff, and if you think I have what it takes, I would say yes. My career as a public school teacher has already come to an early end, largely as result of 21.06, but I never considered the possibility that those circumstances might also give me standing to be the named plaintiff in this kind of litigation. So, yes, I'll do it if your board wants me."

The next day I lit up the telephone switchboards calling all the board members I could reach, starting with Dick Peeples and Lee Taft, telling them that, subject to their approval, our friend Don Baker had agreed to be “it.” Everyone agreed that we could never find anyone better suited to this role than Don Baker.

We introduced Don to Jim Barber, and the two of them began working together on documenting Don's background, preparing press releases, and drafting the petition that would be filed commencing the case. Barber then gave me my next assignment: finding a renowned psychiatrist or psychologist who could give powerful, enlightened expert testimony on the subject of homosexuality. We needed a witness willing to tell the truth at last.

Where to begin? I knew of one psychiatrist in Dallas who counseled a gay friend of mine and who was very supportive, but he wasn’t well known. I decided to try and think outside the box. Who would know the “right” person for this expert testimony, upon which the entire trial could depend? I decided to reach out to a well-connected friend of mine in New York City named Edmund White, a Texas ex-pat who had become well know as the co-author of the famous books “The Joy of Gay Sex,” and “States of Desire" (as well as several novels to his credit). Edmund, who had done a great deal of research for his books on closely-related subjects, did have an idea. He suggested that I try to get the famous psychologist and “sexologist” Dr. John Money at Johns Hopkins University [Founder of the Johns Hopkins Gender Identity Clinic and professor of medical psychology at Johns Hopkins from 1951 until his death in 2006, and one of the first to use such terms as “sexual identity” and “sexual orientation”].

After a series of calls to various offices and switchboards on the Johns Hopkins campus, I was finally able to talk to Dr. Money’s personal secretary and left a message for the professor giving an general rundown of why I was calling. Within a couple of hours, Dr. Money called me back.

“Mike, it’s a Dr. Money on line one,” said my secretary on the intercom.

“Oh, my dermatologist,” I said, cautiously. I closed my office door and picked up the line.

Dr. John Money of Johns-Hopkins University

Dr. Money told me he wanted to find out more about the pending litigation and my own role in it (i.e., that I was part of a foundation seeking to decriminalize same-sex relations through the federal courts, and that I was in search of an expert witness who could talk authoritatively on the related medical/psychological issues involved). I described for him the expertise we needed in a witness from the psychiatric community and asked him if he would consider doing it. His response was interesting. He said he would normally jump at the chance, and that the litigation sounded very important and timely, but that he, himself, was not the best person for that job. He advised that who I needed to contact was a psychiatrist and professor named Dr. Judd Marmor out on the West Coast.

“I tell you honestly,” he said, “that’s the guy you really need to have in that witness chair: Judd Marmor. He’s the former president of the American Psychiatric Association and was instrumental in getting homosexuality taken off the list of recognized mental illnesses in the United States once and for all. He’s the guy you need. He’s who you’re really looking for. He’s out at USC in Los Angeles. Call him and tell him I asked you to make contact. Better yet, I’ll call him this afternoon and tell him to expect your call sometime tomorrow.”

Dr. Judd Marmor of USC/Los Angeles

So that was my new target: Dr. Judd Marmor. I gave it a day and then dialed his number in California. Dr. Marmor took the call and talked with me with great casual charm, calling me by my first name, as if we already knew each other. He agreed to be our witness if we would cover the expenses of travel. I put him in touch with our attorney Jim Barber to seal the deal.

To put it simply, Dr. Marmor was no ordinary human being. He was about 70 years old at this time (the summer of 1981), and he had become widely known in the psychiatric community for the book he co-authored with Dr. Evelyn Hooker in the mid-1960s called Sexual Inversion. That book catapulted him to the forefront of thinking on the issue of sexual orientation. Dr. Hooker recruited him to the task force on homosexuality sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health, which eventually lead to his becoming president of the American Psychiatric Association … in other words he was clearly one of the foremost psychiatrists in the entire nation (I was told once that he was literally "professor emeritus" at 12 different universities).

The APA had classified homosexuality as a “mental disorder” in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for over 100 years. Dr. Marmor had lead the effort to have the American medical community, once and for all, tell the truth about homosexuality. It had, in fact, never been a mental disorder. It was a variation of a purely natural development of somewhere between 3 and 10 percent of the population, depending on how you define it. It occurs naturally in our species, both now and throughout all of human history, and it also occurs in numerous other species, confirming that it is simply a mysterious part of nature. It has no need of “cure” and there is no effective way for it to be “reversed” -- and, in fact, attempting to do so results in significant psychological harm to the individual.

The APA removed homosexuality from its list of mental disorders in 1973 under his leadership. The APA went further to say that the adverse mental health issues among some homosexuals was not attributable to their naturally occurring sexuality, but rather to the pervasive religious condemnation, unyielding social ostracism and bullying, legal discrimination, internalization of negative stereotypes, induced self-loathing, and an almost complete absence of support structures to counter the pervasive rejection faced by gay people in Western societies.

Any other “minority sub-group” of the population (e.g., blue-eyed people, blonds, left-handed people, anyone taller than 6 feet, etc., all of whom are, by definition, “abnormal” because they do not represent the majority) would suffer just as much under their respective abnormal conditions … except that their specific “minority category” is not an issue of interest to the public. What gay individuals faced as repercussions in society was where the harm was being done.

This was the physician who would be our greatest witness.

Dr. James Grigson

Of course, our adversaries in the litigation had their own psychological witness. The representative defendant, Dallas district attorney Henry Wade, hired a so-called “legal psychiatrist” to counter the testimony of Dr. Marmor. He was the notorious Dr. James Grigson, called “Dr. Death” in the media [e.g., Dallas Morning News, June 14, 2004, “James Grigson: Expert psychiatric witness was nicknamed Dr. Death,” by Pat Gillespie, staff writer] on account of his being routinely hired to testify as an expert on behalf of the prosecution of capital crime cases where, in each of his 167 courtroom testimonies, he had concluded that the defendant was irredeemably violent by nature, would certainly commit violent crimes in the future, and thus ought to receive the death penalty under Texas law. [See: The Washington Times, Dec. 20, 2003, “Texas ‘Dr. Death’ retires after 167 capital case trials.”]. In almost all of those cases, the defendants were sentenced to death based on the sworn testimony of this “expert” in psychiatry. He was of course scorned by the greater psychiatric community, because the ability to predict future behavior (from factors such as bed wetting or playing with matches as a child) had been universally debunked as junk science. Psychiatry had proven no more successful than ‘clairvoyance’ in predicting future violent behavior, and the medical community was well aware of this uncomfortable fact. Dr. Grigson’s principal income came from testifying in criminal cases for a steep fee. Dr. Marmor, on the other hand, received his principal income from being a renowned scholar, professor, and an actual practicing physician. The two individuals could not have been more starkly different in character. On the stand Grigson tried to convince the court that one of the principal justifications for 21.06 was that, faced with a possible fine of several hundred dollars, gay people would seek “reparative therapy” to turn themselves into practicing heterosexuals.

Judge Buchmeyer ultimately eviscerated Grigson in the formal legal opinion he published at the end of the case, finding Grigson’s entire reckless testimony unsubstantiated by any evidence, contrary to fact, and literally not credible. As a footnote in history, in 1995 Grigson was expelled in disgrace from both the American Psychiatric Association and the Texas Society of Psychiatric Physicians for “unethical conduct,” stating that he had arrived at “psychiatric diagnosis without having examined the individuals in question, and for indicating, while testifying in court as an expert witness, that he could predict with 100% certainty that the individuals would engage in future violent acts.” [Dallas Morning News, July 26, 1995, article by Laura Bell, Public Health Writer; Houston Chronicle, June 17, 2004, article by Mike Tolson: “Effect of ‘Dr. Death’ and his testimony lingers.”] Grigson sued the APA to block his dishonorable expulsion … and lost. [See: Houston Chronicle, June 17, 2004, article by Mike Tolson, supra.] So Baker vs. Wade presented the interesting juxtaposition of one of the greatest psychiatric scholars of the Twentieth Century against one of the most discredited and disgraced. [See: The Washington Post, Feb. 27, 1981, article by Fred Barbash: “Life or Death: It’s all in Your Mind – or His.”]

Professor Victor Furnish

But finding Judd Marmor wasn’t the end of the road on witnesses for our eventual trial. Because so much of the “societal justification” for so-called anti-sodomy laws (in the minds of law makers) was based upon conceptions of adherence to the Bible and Christian doctrine, we felt we needed a renowned theologian and Biblical scholar to educate the court about the Bible, Christianity, and sexual orientation. We needed look no further than the Perkins School of Theology at S.M.U. We asked Professor Victor Furnish if he would consider testifying on Don Baker’s behalf, and he gladly agreed. He, too, was astounding to listen to on the stand. I had never heard anyone speak with such authority on the historical perspective of the Bible, its actual teachings, and the many antiquated prohibitions and condemnations it contains which, as a civilized society, today’s “Christian Nation” of America simply pretends don’t even exist because they are so clearly irrelevant, wrong-minded and even unconscionable.

He testified that religion has always been that way. We human beings often begin by forming our own personal beliefs on what is right and what is wrong – who is evil and who is good. Then we go to religious references like the Bible seeking individual passages which “prove us right, scripturally.” That process results in Biblical justification for the beliefs we already hold dear, thereby making them supposedly unassailable. But when the Bible “oversteps,” we simply disregard that part. For example, the Bible clearly accommodates human slavery [Deuteronomy 15:12-15; Ephesians 6:9; Colossians 4:1.], so long as they are well treated and the slave holder obtained them without having to capture them from their homelands [Exodus 21:16; 1 Timothy 1:8-10]. For centuries, those passages were the first resort of slavery’s defenders. How could it be wrong if the Bible accepted the relationship between the “master” and the “slave” as normal? Once slavery was banished from the civilized world, those passages, while still present, are simply skipped. Civilization had moved on.

I had always been fascinated by this religious phenomenon of referential selectivity. We refuse to see the Biblical passages that refute our own beliefs, and we hold only to those that support them. For example, Saint Paul suggests in the New Testament that disobedient children should be put to death [Romans 1:30-32]. We don’t accept that, so our churches and ministers skip that verse. Even gossiping is “worthy of death” to Saint Paul [Romans 1:29, 32], but we skip that verse, too. The Bible teaches that the disabled and the blind should not be allowed to enter the place of worship [Leviticus 21:17; 2 Samuel 5:8]. We believe they have every right to be there or anywhere else they want to be, so we skip that verse. It goes on and on.

To Professor Furnish, the several oblique references in the Bible to conduct which today might be understood as homosexual were no different. Even so, Christians love the abstract concept of comprehensively “believing in the Bible” and pretending that they adhere to every word because it was written by God himself … “through the hand of man.” They don’t believe it all, of course, but that concept is so comforting to them that they will make that claim with no hint of irony. Professor Furnish later co-authored a fascinating book on the subject called Homosexuality in the Church.

In addition to these witnesses was Professor William Simon, a renowned sociologist at the University of Houston who had previously studied at the Kinsey Research Institute. He agreed to testify on the negative societal impact of 21.06 on individuals and on the greater community. He was an influential intellectual in the area of human sexualities and co-authored important books on the subject such as Sexual Conduct and Postmodern Sexualities. He played a major role in shaping the contemporary sociology of sexuality and critical sexualities studies in academia. His work helped pioneer a theory of “sexual scripting,” and he was a fierce advocate for sexual tolerance.

"Baker vs. Wade" was filed with the United States District Court in Dallas on November 19, 1979, and quickly became perhaps the primary focus of the Texas gay rights movement throughout the early 1980's, with numerous fund-raisers in all major cities (to help pay legal fees) and donations of time and effort by many attorneys in the gay community.

Technically, the lawsuit had been filed against Henry Wade (the Dallas District Attorney) and Lee Holt (the Dallas City Attorney), seeking a permanent injunction against them which would prohibit enforcement of 21.06 in the city and county of Dallas. A federal judge cannot “remove” an offending statute of the state, but he or she can prohibit its enforcement and effect if it is found to violate the United States Constitution. Wade and Holt were “representatives” of a larger “class” of defendants which included all city, county and district attorneys in Texas. This was done so that any results of the litigation would apply uniformly throughout the state, not just in Dallas County. The Texas Attorney General Mark White “intervened” (i.e., added himself to the case voluntarily) on behalf of the class of state prosecutors; no individual prosecutors intervened.

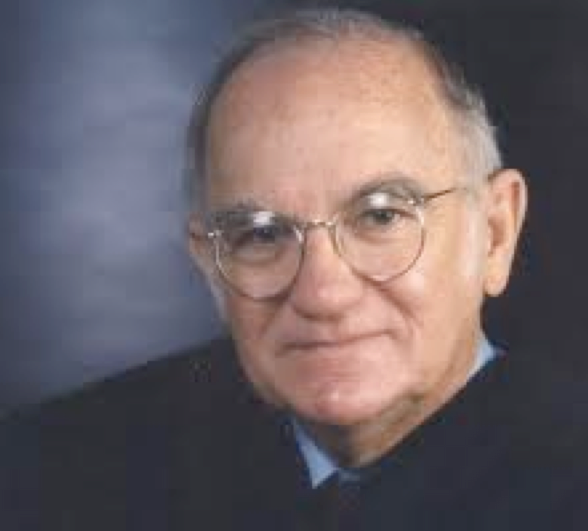

Judge Jerry Buchmeyer

When the case finally went to trial before United States District Judge Jerry Buchmeyer in August 1981, it drew a great deal of public attention and media coverage. No one had ever imagined that the gay community would openly attack the state’s sodomy law in federal court … and mount what seemed to be a professionally orchestrated litigation. Lee, Dick and I attended the trial, but only as observers in the audience. In later years we would talk about how fascinated we were to watch the spectacle of testimony back and forth, while at the same time nervous that some other lawyer colleague might have business in that court and see us in the audience, putting two and two together, and discovering us as gay activists. The early 1980s were “closeted” years, and our fears were not simply imagined. The threat of adverse consequences in our firms (for me and Lee especially … since Dick owned his own specialty practice) was something we lived with.

We waited for a number of months for the judge to issue his decision. We felt confident, but we were concerned with his delay.

In the meantime, sad news befell THRF. As we waited for victory in our great campaign, Mort Schwab, our founder, was diagnosed with AIDS in April 1982 … one of the earlier victims of the disease in the gay-activist community in Texas.

As president and vice president of the organization, Mort and I spoke frequently by phone in order to coordinate and manage the organization's affairs (aside from its financial affairs which were well controlled by Dick Peeples).

Earlier that month Mort had told me that he had been experiencing for some time a strange kind of numbness and partial paralysis in his hands and feet. He said that the doctors thought his symptoms were consistent with a diagnosis of Gillian's Barre, a rare nerve disease in which the body’s immune system attacks part of the peripheral nervous system. He was very concerned about it, naturally, as was I, but he said he was going in for some additional tests to try to find the cause for the malady.

Those additional tests confirmed his HIV-positive status and explained the onset of the neuropathy he was experiencing.

Mort was scheduled to host the next board meeting at his home in Houston. Dick, Lee and I flew down that Saturday morning. It seems ignorant to think of it in these terms today, but I clearly recall, on that flight to Houston, wondering if our spending the day in Mort’s home would contaminate and infect us with HIV as well. No one really seemed to know for sure how the disease spread, but it was definitely contagious. Nevertheless, we would do what we had set out to do and hope for the best. Those days certainly required a degree of courage in each of us.

We were picked up at Houston Hobby Airport by fellow board member (and HHRF cofounder) Steve Shiflett, who regaled us with stories of his flirtatious exploits in the gay bars of Houston the previous night. We liked Steve a lot, but with the threat of AIDS as a contagious disease, probably transmitted sexually, Lee, Dick and I were appalled at his apparent oblivious indifference to the mounting health disaster that was going on right in front of our eyes. This was no time to boast of successful sexual promiscuity. [Steve, suffering greatly from the ravages of AIDS, died ten years later by assisted suicide, on April 17, 1992, at age 39 in San Francisco.].

Lee Taft (left) and Mike Anglin

When we arrived at Mort's house, the other directors had preceded us and were seated in various chairs and sofas in Mort’s living room awaiting the arrival of the all-important Dallas delegation. Mort’s bedroom was upstairs, and, since he was not among the group in the living room, I assumed that was where he was. Just as I began to think that, as vice president, I might need to chair the meeting in his absence, Mort appeared at the top of the stairwell that descended into the living room, sat down on one of the upper steps in order to keep his distance, and proceeded to conduct an otherwise normal meeting of the board.

For years afterwards I wished that we had known more about the virus at that point in time, so that we could feel freer to have him next to us, surrounding him with our affection, support, and best wishes for his recovery, instead of being so afraid and inwardly relieved that he had elected to conduct the meeting from high up on that stairway. Such were the heart breaking oddities of those years.

The lengthy opinion written by Judge Buchmeyer at the conclusion of this long post-trial waiting period (finally signed by the judge on August 17, 1982) still resonates today as one of the most eloquent statements ever written by any court on the rightness of the GLBT community’s demand for equality under the law. [To read the opinion, see: Baker vs. Wade, 563 F.Supp 1121 (N.D. Tex. 1982), rev’d 769 F.2d 289 (5th Cir. 1985) cert denied 478 US 1022 (1986)]. The judge later told his daughter, Pam Buchmeyer, that it was the most important opinion he had ever rendered in his long and distinguished career on the federal bench.

Buchmeyer's ruling in favor of Don Baker and the gay community, however, was short-lived. Winning at the trial court level, in front of Judge Buchmeyer, had been the result of a great deal of hard work at so many levels, but an appeal of the decision would call into play many new special interests and forces determined to keep 21.06 on the books – ready and available as a continuing pretext for discrimination, just as it had always been.

We were informed that the defendants, Wade and Holt, had decided that they would not appeal the trial court's decision. Apparently, if they had needed convincing, the opinion written by Judge Buchmeyer had done the job. However, the outgoing Attorney General of Texas, Mark White, did appeal the decision on November 1, 1982. Then, upon the election of a new Attorney General later the same month (Jim Mattox from Dallas), the appeal by the State of Texas was formally withdrawn. When the withdrawal of this appeal became known, however, resistance to the judgment quickly gained momentum in the reactionary right wing community, for which Texas is, alas, famous.

A new appeal to the Fifth Circuit was filed by Amarillo (Potter County) District Attorney Danny Hill. He claimed to have standing to appeal, even though he had not participated in the trial, because of the formal inclusion of all district attorneys in Texas in the permanent injunction.

The taxpayers of Potter County were not required to fund his efforts to have the Baker decision overturned in a higher court. Financial backing was provided to him by a hitherto unknown entity called "Dallas Doctors Against AIDS." In fact, we always assumed that DDAA had recruited Hill to serve as a place holder to allow them as an organization to, in effect, take the case to a higher court. DDAA was, as D Magazine described the 25-man organization in October, 1985, a "homophobic lobby group" which used the mounting fear of AIDS "like a very big stick, posing themselves in the courts and in Congress for legislative fag-bashing, claiming public safety as their cause." DDAA hired a more-than-willing Dallas lawyer named Charles Bundren (with the law firm of Jackson & Walker) to represent Danny Hill in the appeal.

Don Baker (left) and Dick Peeples (right) heading for the hearing before the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans.

Lee, Dick and I, along with Jim Barber and Don Baker, attended the oral arguments before the en banc circuit court in New Orleans. On August 26, 1985, the Fifth Circuit voted 9-to-7 to reverse Judge Buchmeyer’s decision and uphold the hated Texas statute.

All I could think or way was, “Surely those nine judges never actually read Buchmeyer’s opinion. They simply could not have read it and still reverse him.”

We petitioned for a rehearing but were denied (as we expected at that point). Our victory in U.S. District Court in Dallas had now been lost in New Orleans, in effect, by one vote. Had it been an 8-to-8 tie, the Buchmeyer decision would have narrowly prevailed.

Shortly thereafter it was decided that we would not give up, that the case must be appealed to the U. S. Supreme Court, through a petition for a “Writ of Certiorari.” Importantly, a similar case from Georgia called Bowers vs. Hardwick had also been decided recently and looked like it, too, would be heading to the Supreme Court in Washington.

The costly prospect of seeking this further review by the Supreme Court was the next great undertaking of THRF.

Tom Stoddard of Lambda Legal Defense & Education Foundation

Lee Taft and I were assigned to become engaged in the “National Roundtable” conferences in New York City, hosted by Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund (“Lambda”), one of the chief purposes of which was to have leaders from across the country meet and discuss coordination and funding of the “sodomy cases” to the Supreme Court. The executive director of Lambda at that time was the highly charismatic Tom Stoddard, and soon a strong camaraderie developed between Stoddard, Lee Taft and me as we periodically traveled to New York and deliberated on how to get the Baker v. Wade case, and its companion case out of Atlanta, Bowers v. Hardwick, before the Supreme Court.

Lambda had hired a Harvard law professor named Lawrence Tribe to represent the appellants in the Hardwick case, so Lee and I traveled to Boston to interview Professor Tribe and his assistant, professor Ann Sullivan, in the hope that he would agree to consolidate both cases (Baker and Hardwick) on appeal to the Supreme Court. Tribe and Sullivan agreed to do so, and on January 18, 1986, Tribe filed a request for our case to be heard in the Supreme Court. Before the high court made its decision on whether or not to accept Baker vs. Wade from Texas, the attorneys general of 26 states, including ten states with sodomy laws, urged the Supreme Court to take the Baker case and to sustain Judge Buchmeyer’s original decision in the district court, arguing that Danny Hill’s intervention should be rejected, and the Fifth Circuit reversed, because the decision of a state attorney general (i.e., Jim Mattox) to withdraw the state’s appeal should have terminated the matter entirely.

On June 30, 1986, the Supreme Court handed down it's 5-to-4 decision in the Hardwick case, holding that states were permitted by the Constitution to criminalize private, adult, consensual sodomy if they wished. That ruling, in effect, ended the Baker vs. Wade case by reference, and on July 7, 1986, the court denied certiorari for our case.

As a footnote in history, Justice Powell, who cast the deciding “5th vote” in Hardwick vs. Bowers stated after his retirement from the court (in a presentation given to the New York University Law School) that his vote in Hardwick was the only vote on the Supreme Court he later regretted. He admitted that he had come down on the wrong side of the case. It was too late. His wrong-minded decision lost a great opportunity for the court to bring Constitutional justice to this question a generation earlier than it eventually did.

Our war in the courts was not won with a single case. It was won with a series of three cases.

In 1989 THRF tried again. Five well-known Texans brought suit against the State of Texas in the state district court in Austin, Texas, seeking once again to overturn 21.06, but this time under the provisions of the Texas Constitution … which was, at least in one way, even more protective than the provisions of the United States Constitution. The case would be called Morales, et al., v. State of Texas [869 S.W.2d 941 (Tex.S.Ct.)]

The Texas Constitution had the same protections for all citizens as to privacy, equal protection and the guaranty of due process. But Texas had also passed, as a state constitutional amendment, the famous Equal Rights Amendment which guaranteed that no person’s rights would be abridged on the basis of the sex of that individual. The ERA had failed to become a part of the U. S. Constitution, but it was certainly “the law” in Texas, and still is today.

We had always known that there was a way of seeing 21.06 as a form of simple “sex discrimination” – in the sense of gender discrimination. If “A” and “B” are adults and wish to engage in private consensual sex, they do not violate section 21.06 if A is a male and B is a female. But if B is a male, that private adult activity would be a crime under 21.06. So what is legal for B if a female would automatically become illegal if B is a male. The outcome hinges exclusively on the gender of B under the law. So, “if you’re a girl, it’s fine; if you’re a boy, it’s a crime.” That sounds a great deal like discrimination on the basis of the person's gender.

The plaintiffs who volunteered to participate in the case were Dallasites John Thomas and Charlotte Taft. The other three were Linda Morales, Tom Doyle and Pat Cramer. The group was carefully chosen and wonderfully diverse.

Once again, the case was won in the state district court level. The state appealed to the intermediate appellate court (the “Court of Appeals” in Austin), where the plaintiffs won again on March 11, 1992, the panel of judges holding that the statute was unconstitutional under the Texas Constitution as an impermissible violation of the right to personal privacy. It noted that there was no record of actual prosecution under 21.06 ever since its 1974 enactment. Importantly, the state had admitted the harm done to the individual plaintiffs under the law, but argued that it was, nevertheless, constitutional to have such a discriminatory statute if the legislature so chose. The tremendous opinion written by Chief Justice Carroll weighed heavily the fact that the law’s very existence was obviously to sanction all kinds of discrimination against one sector of the state’s population, and that the state had not met its burden of proof to show some compelling state interest legitimately served by the law.

With another repeat of the pattern, in 1994 the Texas Supreme Court turned us down in a 5-to-4 decision written by John Cornyn, who would go on to become the Texas Attorney General and then later a powerful senator in Washington. His reasoning was pseudo-technical: since 21.06 was a criminal law, he concluded that the case should have been brought in the state’s criminal court system, not in the civil courts. This was clearly a knowingly misleading legal ground for reversal. Guilt and innocence are adjudicated in the criminal courts in Texas. The alleged violation of a person’s civil rights by the existence and effects of a discriminatory criminal statute is clearly a “civil matter” and always has been. Cornyn, as calloused and indifferent to civil rights as Texas politicians have ever come, likely knew that he was using his power to hurt innocent people. But he knew it would be politically popular.

The entire case was thrown out, but not before a wealth of “court record” had been established at the trial level, and powerful opinions written and published.

Once again, the case had been highly effective in meeting our secondary goals of making the legal plight of gay men and women visible and “real” too many intelligent Texans who had never given it much thought, illustrating clearly that the law was a disgraceful pretext for baseless discrimination with no regard for the harm it did in people's personal lives. Newspapers across the state, having become much more educated in the subject area, now openly called for a repeal of 21.06 by the state legislature.

In the third and final attempt to nullify 21.06 through Texas-based litigation, the Lawrence vs. Texas case was brought in Houston. The facts of the case were simple. In the fall of 1998, John Lawrence was arrested by gun-toting policemen who barged into his bedroom, guns drawn, to find him and a friend in a compromising position. They were placed in jail overnight and the next morning plead ‘not guilty’ of violating Section 21.06 at the arraignment hearing.

Lambda Legal (the New York based organization that had worked with THRF in the Baker vs. Wade appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court) jumped on the Lawrence case, and one of the prime leaders of that effort was none other than our old THRF comrade in the Baker case, Lee Taft, who had become the director of Lambda’s South-Central regional office (located in Dallas). Lambda convinced the two men to change their plea to “no contest” and waive their right to a trial. Each was fined $125 by the justice of the peace, an amount high enough to permit appeal to a court of record, the Harris County Criminal Court. There the attorneys demanded that the charges be dropped against the men on federal constitutional grounds, claiming that Hardwick had been wrongly decided. When the court denied those defenses, the two defendants once again plead no contest and accepted $200 fines.

Then the case moved up the ladder to the Court of Appeals in Houston, where it was heard on November 3, 1999. In a 2-to-1 decision issued on June 8, 2000, a panel of that court ruled that 21.06 was unconstitutional, finding (at last!) that it violated the Texas Equal Rights Amendment as sex discrimination. Then the entire Court of Appeals took up the case “en banc” and on March 15, 2001, without hearing oral arguments, it reversed its own panel and upheld the law’s constitutionality in a 7-to-2 decision. Once again we were in the ditch.

A request by the plaintiffs to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals in Austin to review the case was denied on April 17, 2002. Finally, the case was ready for another petition for certiorari, which was filed with the U.S. Supreme Court on July 16, 2002, by the lawyers from Lambda Legal Defense. On December 2, 2002, the court agreed to take the case. Good news which left me both elated and in shock.

At the final hearing in Washington on March 26, 2003, Paul M. Smith argued on behalf of the accused, and the Harris County District Attorney argued, poorly by all accounts, on behalf of the State of Texas. Attorney General John Cornyn decided not to have his office involved since he was in the heat of a campaign for United States Senate. Lee Taft was present in the hearing chamber of the Supreme Court in Washington that day to witness the oral arguments before the court.

Justice Anthony Kennedy

Just three months later, on June 26, 2003, Justice Anthony Kennedy lead the U. S. Supreme Court in its judgment reversing its 1986 Hardwick decision by a 6-to-3 decision declaring at long last that the Constitution did not permit the criminalization of such private conduct among consenting adults. To our great satisfaction, the Lawrence decision relied in part on the earlier Morales case. Justice Kennedy cited the record of the Morales case for the important admission made by the State of Texas in that case that the law was not used for criminal prosecution. And what we also knew with a certainty was that Morales would have never happened but for Baker v. Wade. Morales came out of Baker; Lawrence came, at least in part, out of Morales. Any one case cannot be fully understood independent of the others. Those of us who had lived this issue since the first days of Baker vs. Wade relished the words of the opinion which vindicated us, and Judge Buchmeyer, at last: “Bowers was not correct when it was decided, and it is not correct today. It ought not to remain binding precedent. Bowers v. Hardwick should be and now is overruled.”

Most interesting to me personally, Justice O’Connor’s concurrence was narrowly based on my old “A” and “B” argument. She said the statute violated the equal protection clause because it criminalized male-male but not male-female activities.

Justice Sandra Day O'Connor

Baker v. Wade had presented that legal question just below its surface; Bowers v. Hardwick had not. That was one of the reasons we had always felt it was a mistake for Lambda and the Roundtable group in New York to have pushed Hardwick to the Supreme Court ahead of Baker. Their argument had taken a different logical course. Hardwick presented only a question of the right to privacy. There was no “equal protection” element to that case, because the Georgia law applied equally to all individuals, regardless of the gender of either participant. Baker contained both “privacy” and “equal protection” issues, because the Texas law was narrowly focused only on same-sex couples.

Many at the Roundtable acknowledged this important distinction in the two cases, but worried that “If we take Baker up first, and lose, then all will be lost for another generation. If we take Hardwick up first, and lose, we only lose on privacy. We would still have the unresolved question of equal protection of the laws available to use in a second assault on these laws.” So, in the end, that was the argument that won out. Keep “equal protection” in our back pocket for now, and just hope to win on the single question of “the right to privacy” with the Hardwick case. However, when the court decided Hardwick, it also issued an order that it would not take up Baker on some later date as we had requested … holding that it had become moot with the holding in Hardwick (which was not entirely accurate, of course).

But, with the Lawrence decision, that was all behind us now.

The war against 21.06 was finally over – and the results would be effective in all 50 states immediately. After 23 years of struggle (from the inception of Baker vs. Wade to the conclusion of Lawrence vs. Texas) the complete jurisprudence on the criminality of same-sex relations had been reversed by the highest court in the land.

We knew, too, that the elimination of “criminality” for the GLBT community silently opened the door for new issues to be at last tested and resolved in our favor, hopefully, through political action (like statutes and ordinances rewritten to include the GLBT community in assurances of non-discrimination in housing, public employment, public accommodations, etc.) … through new court rulings (such as the constitutional right of same-sex couples to marry and to have their marital unions recognized and respected equally across the country) … and through new executive orders (such as the right of duly qualified GLBT men and women to serve openly in the U.S. military).

All of that would, or at least could, come in time, but it had always been our view that the new freedoms and protections that would follow on the heels of Lawrence would have forever been denied to us … unless and until the state criminal laws like 21.06 were finally and completely evisserated. It was done.

As we get older, it seems that history does not matter as much. At least the careful regard for history seems to dwindle in the public mind over an expance of time. A younger generation of GLBT youth, and then the next, all growing up in a world where it is simply unthinkable that their natural sexual life could be considered criminal – as if that were something that might have happened in Uganda or back in Medieval Europe.

Once rights are won, and that generation of “old soldiers” passes away, the story of the struggle for those rights becomes more and more irrelevant and tedious to the younger audience. Lee and Dick and I were three of the core leaders of a collection of volunteers who changed our society for the better across the face of America, and yet, even today we are uneasy. We know how quickly tides can change. We are constantly reminded of this by the fact that 21.06 is still, today, “on the books” of the Texas Penal Code. Standing there ever-ready to go back into full force and effect the moment the United States Supreme Court becomes populated with one or two more justices of he ilk of Scalia or Thomas or Alito. In June 2019, Justice Clarence Thomas openly called for a “review” of the Lawrence decision, calling it “wrongly decided” … literally inviting challengers to bring up a case calling for a resurrection of “the states’ right to criminalize same-sex activity.”

So, to correctly visualization what "the Three Texas Cases" stand for today, think of three dominos. Stand the first one on its narrow end so that it is upright. That is Baker. Take the second domino and carefully place it upright, on top of the first. That is Morales. Take the final domino, Lawrence, and carefully place it, upright, on top of the second domino. Now you have the proud tower of "the Three Texas Cases" that changed our world.

But see how that tower stands? It is perfectly balanced today, and it will continue to stand so long as there is not the slightest motion against it. But under the current polarization of the American Left and the American Right, the “wind” that could easily topple that beautiful tower, in the blink of an eye, is a vote of a more conservative Supreme Court, issuing a gentle and innocent-sounding ruling that, technically, Lawrence was wrongly decided (as now declared by Justice Thomas) and that, as silly and odious as state sodomy laws may be, that kind of regulation of society is much better left to the sound discretion of the 50 state legislatures.

With such a decision, which is not impossible, everything would change again. Section 21.06 is sleeping there today in suspended animation, still in the Texas statutes, waiting for automatic “reactivation” as an enforceable provision of the Texas Penal Code if Lawrence is ever set aside. No act of the legislature would be required. No consenting signature of our governor would be needed. By the stroke of a pen in Washington’s high court, we would be returned, legally, to the late 1970s, with little or no hope of convincing our current state government to rethink this law and remove it legislatively.

Of course, Lawrence is not alone in that exposure to sudden reversal if the present balance of the court shifts. The same could be said for Roe v. Wade, and certainly for the Obergefell and the Windsor decisions that ushered in the new age of legalized same-sex marital unions.

Two of the "old soldiers" ponder what the future holds for all of the new rights achieved in the federal courts (Mike Anglin, left, and Lee Taft, right)

That is what we, who were lucky enough to live into older age, often ponder and worry about. It is always on our minds, a kind of “watchful waiting” to see if Lawrence can flow through turbulent times without toppling in the rough currents of modern day American politics.

So isn’t that the ultimate question today? If something were to happen, if Lawrence is ever (god forbid) repudiated and stricken down by a new, more conservative court, what would be the response of the younger generations of GLBT men and women coming up behind us? What would they do? Would they rise up? Would they commit their “lives and personal fortunes” to do whatever it might take to gain back the rights that were lost? Or would they just stand back and try once again to quietly “live within the law” by going undercover, hoping to “blend in” … to become undetectable, as so many had done in previous generations? And what would the vast community of our straight allies do? Would they grow strangely silent, like the “good Nazis” of the 1930s in Germany?

History is unrelenting. It can be forgotten, and, with the passing of enough time, must often be painfully re-lived. The same lessons must be learned again, always through human suffering, and the same struggles must be taken up again, always at great personal cost. Will there ever be a second “war” on 21.06? That is what we tired old soldiers often ponder today.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Endnotes:

Ø Morales opinion, Court of Appeals - Austin: http://www.leagle.com/decision/19921027826SW2d201_11010/STATE%20v.%20MORALES

Ø Cornyn opinion in Morales, Supreme Court of Texas: 869 S.W.2d 941 (Tex. 1994)

Ø Lawrence v. Texas, 539 US 558 (Supreme Court 2003-06-26). The opinion can also be easily found at: http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/02-102.ZS.html

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Excerpted from: Beings of a Golden Kind, by Mike Anglin. © 2017 by M. W. Anglin